‘Tis the time of penultimates.

Today marks the second-to-last stop on our several-month blog tour. So come check out my interview at Lisa Haselton’s Reviews and Interviews for a bit of fun and a chance to win.

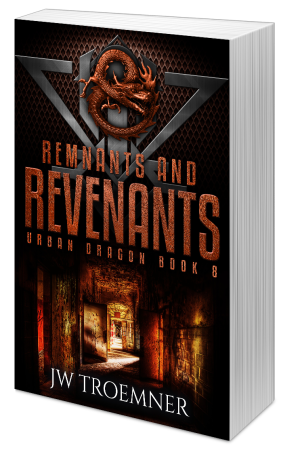

Saturday also marked the release of Remnants and Revenants, the second-to-last book of the Urban Dragon series. I hope you’ve been feeling nostalgic, because we’re going to see some old faces again– along with some old monsters.

Saturday also marked the release of Remnants and Revenants, the second-to-last book of the Urban Dragon series. I hope you’ve been feeling nostalgic, because we’re going to see some old faces again– along with some old monsters.

That’s right, there’s only one book left. But if you’d like to get a sneak peak at it, the Volume 3 compilation will be available on Saturday, just in time for Christmas. It’ll include the last three books of the series, along with a deleted chapter to shed a little light on the past.

Leave a comment